Religion in the Totalitarian Past: A Report from the Seminar and Reflections on the Topic

Author: Volodymyr Volkovskyi is a Ukrainian philosopher, a specialist in religious studies, and a Research Fellow at the H. S. Skovoroda Institute of Philosophy of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine

The Eastern European Institute of Theology has launched a series of theological methodological seminars under the umbrella title “Public Theology in the Context of Overcoming the Totalitarian Past.” The aim of the seminars is to analyze the experience of the totalitarian and colonial past in Eastern and Central Europe, to study its consequences for contemporary social and political processes in the region, and to outline a public theology that can contribute to the deconstruction of the totalitarian and post-totalitarian experience and to the building of sustainable democratic structures.

The first seminar, “Totalitarian Past: The Case of Eastern and Central Europe. Political, Social, and Ecclesiastical Aspects,” was held on May 10. It was devoted to strategies for the existence of churches and religious communities in totalitarian states.

It is quite surprising to see fascinating events that bring in truly top-notch speakers and experts go by without much publicity and remain in obscurity despite the high numbers of participants. This can be said about the series of methodological seminars by the Eastern European Institute of Theology under the broader title “Public Theology in the Context of Overcoming the Totalitarian Past.” However, the totalitarian is not the “past”. It is, unfortunately, the present, and the question remains whether it will be the future.

The first seminar on “The Totalitarian Past: The Case of Eastern and Central Europe. Political, Social, and Ecclesiastical Aspects” focused on the survival strategies of churches and religious communities in totalitarian states. This included not only the USSR but also Romania and Yugoslavia. It brought together outstanding researchers from Ukraine, Finland, Romania, and Britain. The seminar was divided into three segments: a foreign segment on the fate of various churches, a Ukrainian segment on the fate of churches in the USSR, and a philosophical segment with a lecture on totalitarianism as a phenomenon.

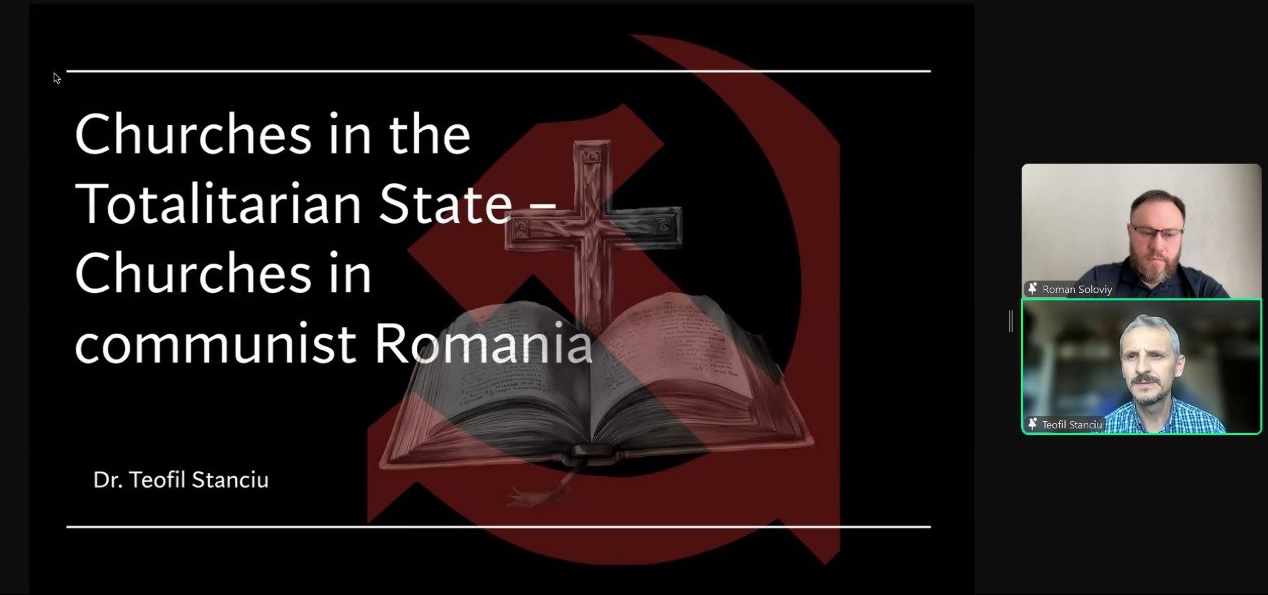

Romania

The first segment delved into the survival strategies of Christian churches in Yugoslavia and Romania, with a particular focus on the fate of Protestant communities, driven both by the Institute's confessional leaning and the interests of researchers. Romanian history was presented by Teofil Stanciu, translator, book editor, director of the publishing house Decenu.eu, lecturer at the Eastern European Bible College (Oradea, Romania), and member of the Program Leadership Team of the Osijek Doctoral Colloquium.

After briefly introducing the history of Romanian Christianity and the Romanian Orthodox Church, he described the history of evangelical Christians, particularly Baptists, in Romania. To summarize without reprising the entire rather interesting report, the fate of Baptists in Romania was not easy even before the communist regime, both during the Kingdom and the Iron Guard, and in the times of Antonescu and Ceauşescu. For a long time, the Baptists were not recognized as an official religious organization (“association”); only in 1933 did they receive partial and, in 1946, full recognition. Pentecostals were never recognized under pre-Soviet Romanian rule. The communist authorities tried to establish control over religious organizations and, therefore, created centralized religious organizations under one roof.

According to the lecturer, the “hard times” turned into the “dawn of a dark sun” when the communist authorities employed various approaches to tame and control religion. The Greek Catholic Church was completely dismantled, the Romanian Orthodox Church received a loyal pro-Communist patriarch and actively collaborated with the regime, and the opposition was eliminated. Evangelical churches were persecuted, while Baptist churches were merged into one organization controlled by the authorities. Eventually, Pentecostals were recognized and even allowed to establish an institute in Bucharest.

Thus, attitudes toward churches varied from outright persecution to a strategy of control and centralization (a handful of remaining Orthodox educational institutions and created neo-Protestant confederations served as centralized control networks) and ultimately to the exclusion of religion from public space and discourse. In turn, the churches took different positions: cooperation, full support, submission or going underground, and outright opposition. It is worth remembering that the Romanian regime differed from the Soviet regime – it combined Maoism and neo-Stalinism of a peculiar domestic form, a distinctive Romanian national communism.

But despite the waves of arrests and the gloom of the 1980s, religious communities resisted. The lecturer recalled the Great Revival from Oradea (1972-1974), Billy Graham's visit in 1985, letters of protest from Christian leaders, and Romanian immigrants' addresses in the U.S. Congress.

But the modern Romanian church and religious communities in general are in a rather difficult situation, facing the question of what to do with the totalitarian past and how to reflect on it. On the one hand, there is this romantic aura of martyrs and heroes. On the other hand, those who collaborated with the regime are often in power in religious communities. The Orthodox Church prohibits access to the archives of the Romanian security services. How to tell who is who? And what conclusions can be drawn from this?

How can heroes of the faith be distinguished from political opposition (e.g., priests who belonged to the Iron Guard)? Finally, when, how, and who has the right to judge and make that distinction? Should everything just be forgotten? This is quite problematic because it raises the question of how to bear witness to Christian truth in society after all of this. And how can society trust the accomplices of terror?

Yugoslavia

Andrej Bukovac-Mimica, a doctoral student at the University of Helsinki and a lecturer in church history at the University Center for Protestant Theology Matthias Flacius Illyricus at the University of Zagreb, continued this topic on the Yugoslavian front.

After giving the historical context of the primarily Croatian part of the former Yugoslavia, the speaker presented the history of Protestant churches recognized by the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1930, including ethnic Slovak and German churches of Augsburg recognition. By analyzing the 1953 Yugoslav law on the legal status of religious communities and its application, he showed the resistance methods that were in many ways similar to those in Romania yet had significant differences. Tito's regime was unlike other communist regimes in its comparative lenience, especially with regard to religious organizations. However, it still employed typical totalitarian methods in attempts to control them in one way or another.

The Underground Greek Catholic Church in the USSR

The second segment, titled “The Experience of Underground Christianity in Totalitarian States and Its Impact on Modern Churches,” featured Ukrainian speakers who highlighted the fate of Christian churches in the USSR in their reports. This fate was neither simple nor easy. These three speakers touched on three denominations – Orthodox, Greek Catholic, and Baptist.

The situation of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was the simplest, as described by Fr. Taras Bublyk, PhD, senior lecturer at the Department of Church History at the Ukrainian Catholic University. He explained that it was outright banned and destroyed. The Ukrainian Catholic University’s Institute of Church History contains over 2000 interviews with priests of the underground Greek Catholic Church. Fr. Taras recounted this tragic history – from Kostelnyk to the emergence from the underground; the strategies used by the church were twofold: avoidance and mimicry. The underground church tried to preserve its hierarchy above all else, including by appointing secret bishops. The laity played an active role, often taking the brunt of the totalitarian system’s brutality by defending the priests. However, most of the priests who were members of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) in 1946 made compromises with the Russian Orthodox Church and the USSR, which, if anything, could be expected.

Fr. Taras noted that the history of the underground church still influences discussions within the UGCC about its identity.

The Orthodox Church in the USSR

By comparison, the situation in the Orthodox Church was somewhat different, as described by Serhii Shumylo, a Ukrainian historian and religious scholar, cultural and public figure, journalist, PhD in History, Director of the International Institute of Athonite Legacy, researcher at the Institute of History of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and visiting researcher at the Department of History, Religion, and Theology at the University of Exeter (UK).

Shumylo mentioned that he spoke from his own communication with people from the Catacomb Orthodox Church who were participants in those events. He has also written a book on this topic, "In the Catacombs. The Orthodox Underground in the USSR."

Due to the monopoly of the Russian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate (ROC MP), there is a stereotypical perception that the Orthodox Church has compromised on a massive scale. As such, there is a myth about the Orthodox Church's alleged innate servility and subordination to the state. In fact, the history of Orthodox resistance shows that this is far from the case. The speaker covered an extensive history of this struggle, so I will only summarize a couple of conclusions and ideas.

The bulk of the Russian Orthodox Church adamantly opposed Soviet rule. The 1917 Council was won by the very “party” that had been lobbying for the independence of the Church and disgust with Caesaropapism during the last decades of the Tsarist era. To break down the first level of defense, the Soviet government had to create the “renovationist movement,” wait for the death of Patriarch Tikhon, and then terrorize Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) into signing the “Declaration of Loyalty to the Soviet Authorities” (1927). In the end, it did not help – total repression began against all those who did not submit to Metropolitan Sergius as Primate, and it lasted until 1943. Stalin had to build the modern Moscow Patriarchate from the ground up. Various denominations that refused to cooperate with the regime were subjected to the most severe terror. The strategy of the USSR has always been based on the creation of a controlled puppet centralized structure and the destruction of the elites (hierarchy) of the uncontrolled. As a result, most non-conformers lost their hierarchy and then had to restore it through other Orthodox Churches (such as the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia).

However, if I may make a follow-up comment on Shumylo’s presentation, the protest groups of Russian Orthodoxy, despite their protest against the totalitarian regime, were and are extremely traditionalist and anti-ecumenical. Even though they have experienced the devaluation of official “canonical” statuses, they still cultivate a largely traditionalist approach. Therefore, the question arises as to which is more important, traditionalism or Orthodoxy itself. Instead of realizing the error of certain points of ecclesiology, they continued to sequester.

It is worth noting that Serhii Shumylo has published a lot on this topic, so discussions can undoubtedly continue.

Evangelical Baptists in the USSR

Olena Panych, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, described the situation of the Baptists as markedly very different. The Baptists had no sacramental hierarchy and were less dependent on the ordination structure. Nevertheless, the policy of the USSR – as Panych spoke primarily about the 1950s and 1980s – was also based on the principle of creating a controlled centralized umbrella structure and harsh repression against all those who did not join it. The USSR, in its later years, however, recognized that believers indeed existed but tried to do everything possible to prevent religious organizations from growing and to educate the younger generation in the spirit of “scientific atheism.” However, after the Twentieth Congress, the USSR proclaimed that it was under the rule of “socialist law,” not “revolutionary law,” in particular, that only specific criminal acts proven in court could result in an arrest.

The history of Baptist churches in the USSR is marked by this tension between the official All-Union Council of Evangelical Christians-Baptists (ACE Baptist) and the Council of Churches of Evangelical Christians-Baptists (CCECB), established in 1965. This was preceded by a history of the Soviet authorities demanding that the official Baptist Supreme Council minimize preaching, limiting it to “meeting the religious needs” of existing believers, essentially prohibiting preaching and church growth. “Disobedient” churches were punished by revoking or denying official registration, and as a result, the concept of registration was immensely devalued in the eyes of the Baptist Church.

In 1961, an initiative group was created, headed by Baptist leaders Gennady Kryuchkov and Alexei Prokofiev. It aimed to convene an extraordinary all-Union congress of the Church of Evangelical Christians Baptists. Although formally their demand did not contradict even Soviet legislation, it provoked harsh repression, and the internal church opposition rapidly turned into a church split (the creation of two parallel structures) and political dissent.

The strategies of resistance were “classic”: petitions, complaints, a demonstration in Moscow in 1965, collecting materials about the persecution of believers (violations of rights and imprisonment), and appeals to international organizations. Later, an extensive network of underground book printing was created, as was the Council of Relatives of Baptist Prisoners as a human rights organization.

Оlena Panych spoke about prominent personalities from the history of Baptist resistance: Lydia Hovorun, Lydia Vins, Georgii Vins, and Joseph Bondarenko. George Vins was deported from the USSR, and other leaders were persecuted, but the Baptist churches of the CCECB movement continued to multiply. The lecturer noted that the Baptists acted admirably in court, referring to human rights, Lenin's works, and the Bible and protesting against the legislation itself; their self-represented defense was grounded both theologically and politically. That’s when the position was formed, which, according to the lecturer, is still popular among Ukrainian Baptists. It can be summarized as follows: “All authority is from God, but not all authorities are of God, because God sets authorities so that the faithful can live a righteous life, and if the authorities do not fulfill this function, then there is no reason to obey such authorities.”

On the other hand, the majority has always been inclined to cooperate, and resistance is a matter for the few. In addition, the ACE Baptist benefited more from the work of the initiative movement than the “initiators” themselves. The authorities made concessions, but only to the “loyal” Baptists, allowing the rescission of controversial documents, etc.

Repression and registration denial resulted in some churches, especially Ukrainian ones, actually separating in the 1970s and creating a movement of autonomous registered churches (now headed by S. M. Shaptala, the son of the then-head of the ACE Baptist).

It is worth noting that the “national factor” was not applicable to Baptists, unlike the Orthodox or Greek Catholics. The Evangelical Christian Baptist movement was originally an all-Union, nationwide movement; regional differences were secondary, and this is still reflected in the language and ideas circulating within it. Finally, Olena Panych emphasized the counterpoint of structure and agency – how a person can change a system.

What Is Totalitarianism and Is Ukraine a Colony?

The third section was led by Taras Lyuty, a Ukrainian philosopher and writer, philosophy and religious studies professor at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, and a researcher at the H.S. Skovoroda Institute of Philosophy. In his lecture “Particulars of Totalitarianism in the Context of the Confrontation between Empire and Colony,” he ventured to summarize the various strategies of totalitarian regimes' impact on society (and, in particular, religion) and raised the question of whether Ukraine can be viewed as a colony. Now, I’d like to briefly summarize Lyuty’s talk and add some of my own thoughts since this is the topic of my research as well.

He began his presentation with Karl Popper's The Open Society and the “main predecessors of totalitarianism” Plato, Hegel, and Marx. Totalitarianism begins when a closed society is formed, where the government (the state) tries to control everything and everyone. However, the roots of totalitarianism are not only in the desire for absolute power. Totalitarianism is possible only in the Modern era. Firstly, because technology makes mass control possible. Secondly, because it was modern science, modern philosophy, based on the ideas of the Enlightenment and rationalism, that naively believed in the pervasiveness and absolute accessibility, controllability of reality. The idea of remaking everything based on Reason, the belief that we, rational beings, are capable of “improving the earthly world” and even human nature, led to totalitarianism.

Figuratively speaking, totalitarian regimes do not have as much Nietzsche or Schopenhauer as they do Voltaire or Hegel. This naïve belief that science can know and do everything, multiplied by the irrational will to power and the technical ability to realize it (the same “uprising of the masses” of Ortega y Gasset), paved the way to totalitarianism. To paraphrase the words of V. Ern, mentioned by Lyuty in his lecture, the “spirit of Kant” speaking through the guns of Krupp (a German arms manufacturer of the early 20th century) might not be a definite fact, but Hegel is absolutely there.

It is not surprising that the centers of “irrationality” – art, religion, and culture – become major hubs of resistance against totality and totalitarianism. However, the point is not in (ir)rationality but in the attitude to nature. Totalitarian ideology ignores nature; it seeks to seize it, subdue it, and mold it to its liking. Wherever there is this contempt for nature in the name of an idea, there is a threat of totalitarianism.

The issue of totalitarianism is inseparable from the issue of imperialism and colonialism. Lyuty reminded us that many people do not want to accept that Ukraine was a colony. “Look at the real colonies!” they exclaim. However, if we analyze Russian attitudes toward Ukrainians, they are quite colonial. First of all, Lyuty notes, referring to V. Ern's book about Skovoroda, that Russians treated “Malorossiya” as a wild, uncivilized, backward land where they supposedly bring culture. The “great Russian culture” and “world civilization” were contrasted with “peasant rituals and superstitions,” “wild barbarism, anarchy, and violence.” Despite the nuances of the 1920s, everywhere and always, the Russian people were given a primary, dominant role, which can be seen very well in the anthems of the USSR republics. Ultimately, the West intuitively understood that “Soviets” was at least politically equal to “Russians.”

Here, I can only add my thoughts, which I hope will be published in English one day. Several features characterize the colonial attitude toward the other. First and foremost, it is an attitude based on a collective, communal characteristic. It is always a subordination, a hierarchy, “above/below,” with the socio-cultural hierarchy competing with the economic hierarchy (“a rich black man is not above a poor white man”). In the colonial attitude, the object of discrimination and segregation is primarily the collective identity. Two types of colonial attitudes can be distinguished: when the discriminated attribute cannot be altered (e.g., skin color) and when it can (language or ethnic identity). Obviously, Ukrainians fall into the second type – although, again, the language attribute was quite strong (Shevchenko's “maybe father sold the last cow... [to pay] for the learning of the Moscow language”).

Announcements or Conclusions?

However, I don’t want to rush and tip my hand.

The seminar series continue, and on June 10 Mykola Riabchuk, a well-known expert in this field, will lead a discussion on colonialism and Ukraine.

Of course, everyone interested in the discussion is invited to register on the Institute's website here.

The key thing is to remember to join the seminar once you register. That’s a tip from yours truly, an expert scatterbrain.